I’m old enough to remember a time before ATM’s, cell phones, the internet, and portable computing in any number of form factors. No, there were no dinosaurs stealing my school lunch, and I didn’t learn to write on a clay tablet with a stick (despite what my now grown children might think). But the depth of my field of vision extends back to some of the earliest arrivals of the computer and information technology advances that made their way into our everyday lives. Considering those technologies, and how they came to become ubiquitous to daily life today, offered some insights into the nature and challenges cyber security professionals must now address. We laid the behavioral groundwork to enable malicious actors, malware, and cyber-crime. We also helped foster a culture of trust that made cyber risks seem unlikely. And we continue to pay the price today. So, let’s step back today and look at where we were, how we got here, and what we can do about it tomorrow.

Once upon a time, people paid cash for their purchases. Credit cards were few, and the idea of “paying on time”, even through a credit card, was shunned whenever possible. So when people needed cash, they went to a bank, stood in line, and interacted with a bank teller. If they were not well known by their branch staff, they had to produce identification on the spot. Simple, safe, secure. Then ATM’s were introduced. They offered convenience, and were accessed using a plastic card indistinguishable from a credit card… familiarity, acceptance. Early ATM’s were often called cash machines (or automated teller machines) because they did little else but display balances and dispense cash. (Human Tellers did more). And using a card to gain access, coupled with bank marketing of the convenience and ease credit cards offered, began our love affair with both. The growing foundation of computerized account management, transaction processing, and funds transfer made possible by investment in mini and mainframe computers in central data centers, joined through dedicated communications networks, made everything seem effortless. And safe and trustworthy. There were humorous stories of people trying to “rob” ATM’s by hauling them away only to have the ATM yank their truck axles from under them… Credit card fraud was rarely reported. Everything was secured by 4 digit PIN’s, or maybe slightly longer ones used by a cautious few. “Good people” everywhere used both technologies.

Scaling computers down to tabletop or desktop size, complete with software to do useful things like record and manage financial and statistical data, automate document production, and prepare visual representations of ideas, plans, and results positioned them as work machines. Graphical user interfaces made them approachable by people outside of business, but they remained isolated tools for specific tasks. Dial-up services provided early access to remote resources, and exposed machines with no security provisions aside from a user ID and password to open an onboard account to anonymous access from afar. One week after my first purchase of a travel map from a dial-up service, my credit card was compromised, though the event was caught by my bank. Even then, in the 1980s banks had begun to monitor user credit card buying patterns and flagged suspicious out-of-pattern behavior. Banks had always evaluated risk as part of doing business. Customer computer use for retail events was just another risk. They had a jump, for the time being, on this emerging phenomenon. But people had no frame of reference, no history, and little or no available education about the possible cyber threats developing in parallel to the technology. Events were isolated, and often investigated, “handled”, and filed away, unreported outside the impacted organization. Education and awareness were limited to the small population of curious and aware computer scientists.

Computer viruses came into being in the 1980s too, first passed through shared disks, then, online boards and services, and finally, with the arrival of the internet, they achieved mass distribution. Steve Jobs may have thought he changed the world with the introduction of the first Macintosh, and its user-friendly graphical user interface, but Tim Berners-Lee and all those who contributed to the internet gave everyone a reason to have a computer, and to use one. With the internet, email, and electronic commerce, retail (in specific), brought convenience to the public once again. Chat followed email, first as an add-on, and later as a stand-alone application. Communication to anyone anywhere became quick, simple, and affordable. Shopping became easier than going to the mall, as working hours and family demands created lifestyles and needs outside traditional retail hours. It was like the invention of the telephone all over again, but now with pictures, products, video and so much more; and it was interactive!

But these feature and service advances rapidly outpaced consideration, attention, and effort to make them safe and secure. New software technologies, then called object-oriented programming, led to thoughts about new platform architectures where small dedicated programs called “apps” would define the overall utility of a computing device. Security was not at the forefront of the promotional seminars and workshops I attended on these advances. All too often I sat in meetings where security staff with awareness of cyber risks were silenced as the “product prevention” people, always asking that projects slow down to engineer security provisions into new designs and new product or service features from the start. But, in the rush to be first, to be better, to compete in a fast-paced marketplace of rapid innovation, developers and management everywhere adopted product development methods based upon multiple successive iterations to refine offerings, often leaving security to a “future release”. Scant start-up resources were prioritized to deliver competitive edge, and security was not in the public’s mind as a competitive feature. The “homes and businesses” were going online fast, with unlocked doors and open pathways to personal and financial information. It did not take long for malicious actors to begin to realize what was there for the taking, and begin its harvest in earnest.

Cyber criminals, first individuals or small groups of actors, later forming more organized and professionalized groups, were more technologically sophisticated than the user population they exploited. And, early on, services and firms did try to first warn and defer responsibility for security onto the user. Market resistance defeated that effort in relatively near term. As increasing awareness of viruses created demand, anti-virus and other security software products made way into the marketplace. Even novice end users began to be aware there were risks associated with online computing. Hardware vendors bundled anti-virus software with new computer purchases. Revenue streams were created to assure continual streams of updated anti-virus signature data to keep these products current and useful. Financial institutions, with much to lose, were often at the vanguard of security and cyber risk response, leveraging their past efforts to strengthen rules, user education, and protective technologies to detect, deflect, and recover from cyber intrusions. Multi-factor authentication and strong passwords became common features. News media began to investigate and report cyber breaches and crimes that threatened users’ ability to maintain and control their own personal identities. Horror stories of identity theft, financial loss, and the difficulties of recovery become commonplace. We had trusted too long, and paid too much for convenience.

Today the marketplace is much more aware of the risks associated with cyber activity. Security is a competitive advantage. Legislation governing breach reporting requirements is in place in every state, though no Federal law is currently on the books. Cyber security and risk management have become an important component of product and service development, at least more so than in the 1990s and early 2000s.

But we still repeat some of the mistakes of the past. Smart phones, other mobile devices, and social media’s rapid rise to ubiquity all too often have followed the path and errors of their larger desktop and laptop cousins. Security was not always a top priority, and today there are still concerns about shared data across apps and hacked access into smart phones though near field point-of-sale terminals, or social media platforms. Those issues are still being worked today. Device security is getting stronger. As mobile devices extend and blur the boundaries of corporate enterprises tools, processes and technologies are following closely to help manage and police device configurations, activity, authentication, and authenticity. App sources now scrutinize new product candidates for security provisions before publication.

Those processes are not perfect. The technologies underpinning social media platforms remain largely open and rich with aggregated user data subject to distribution and repurposing agreements that drive revenues under the radar of most users. Attorneys protect their client firms with vast, detailed end-user license agreements (EULA’s) that few read and fewer fully understand. But these platforms remain rich, inviting targets for malicious actors. User data, more than any other form, has truly become a form of currency with value at least the equal of any bitcoin.

The matter does not stop at social media and mobile platforms. Artificial intelligence creates an opportunity for gleaning more useful data from raw forms. Monitoring devices on streets, in stores and homes, in cars, and recently now at airplane seats are gathering more and more raw material to share with firms that will cultivate it into value and revenue streams. These technologies and practices open questions about individual privacy, ownership, and law. They also carry their own forms of cyber risk. Once again, now and in the foreseeable future, cyber risk and security professionals will need to continually evaluate, develop and refine processes, education, and technologies to identify, measure, and manage these risks as they enter modern life throughout developed and developing societies.

We have reached a point where the pages of technological advance, security, and cyber risk, must now turn as one. Cyber risk and security must take advantage of artificial intelligence, monitoring, and social platform management technologies too. Detection and identification of cyber threats will gain complexity as data gathering and repurposing gains diversity and complexity. Risk and security professionals must ensure the foundations of their programs form a solid basis for extended scope and sophistication in the future. Frameworks, tools, procedures, and processes will all be important attributes of any cyber risk program. Lawmakers, legislators, and ethicists also need to weigh in on how best to enable progress while preserving some reasonable level of personal privacy and safety.

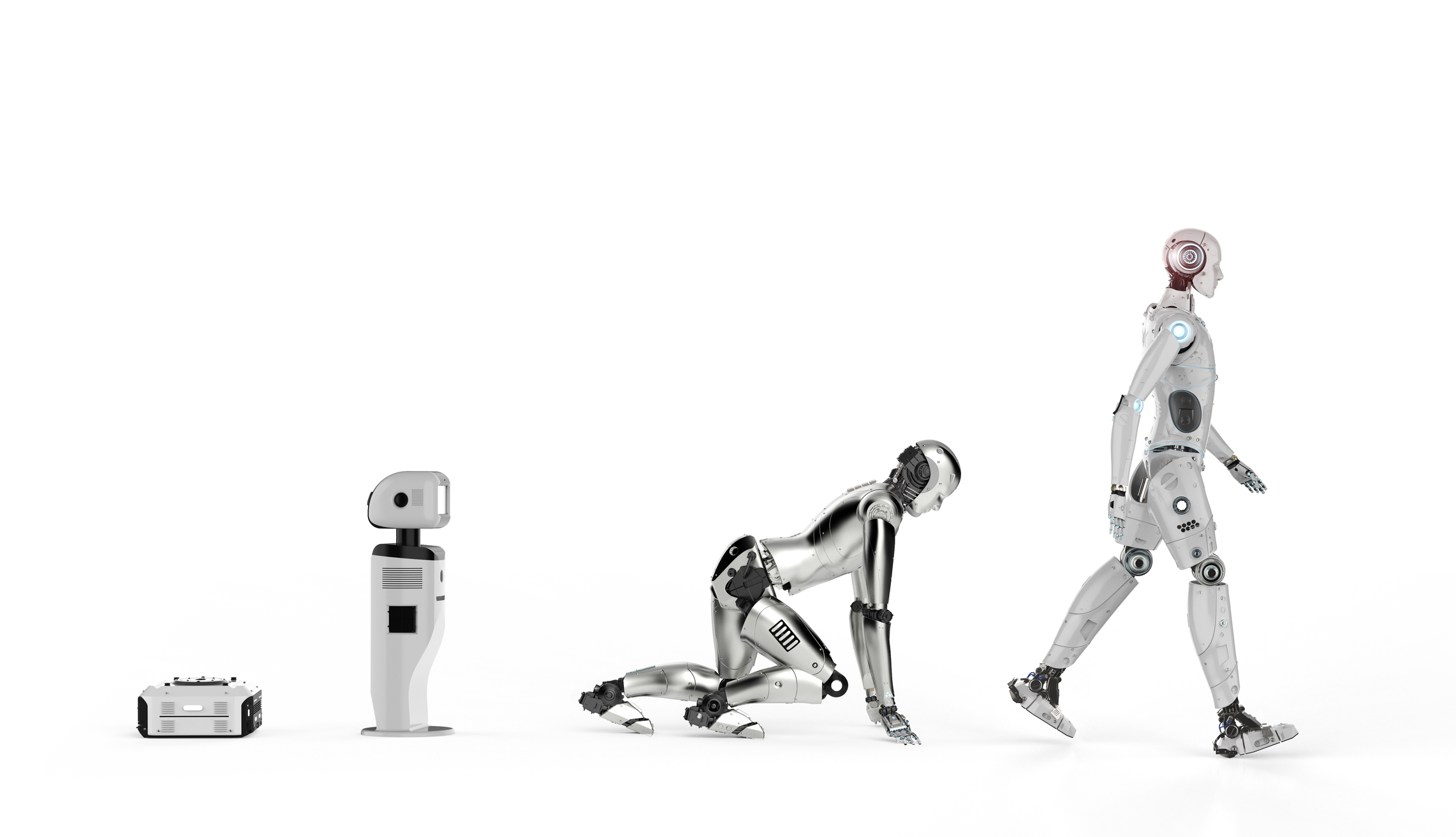

It’s a long way from the stand-alone piece of automated machinery to our interconnected “smart” devices and practices. There is a dependence upon many connected services now, for finding our way in cars, keeping track of important dates, making purchases, staying in touch, and on and on… the list continues to grow, as does our dependence upon these technologies, ones to come, and the data cache it all creates. Now everyone, users, makers, security folk, lawmakers, and even apparent bystanders must become equally “smart” about security and managing the associated cyber risks of an ever-connected society.

About the Author:

Simon Goldstein is an accomplished senior executive blending both technology and business expertise to formulate, impact, and achieve corporate strategies. A retired senior manager of Accenture’s IT Security and Risk Management practice, he has achieved results through the creation of customer value, business growth, and collaboration. An experienced change agent with primary experience in financial, technology, and retail industries, he’s led efforts to achieve ISO2700x certification and HIPAA compliance, as well as held credentials of CRISC, CISM, CISA.